The exhibition itself is a multi-dimensional curation of fashion and fashion history. While the costumes spoke for themselves visually, the Period Rooms drew the audience back to their historical contexts. The accompanying furniture, setting, music, lighting, and ambience contributed to a highly effective simulation of the historical venues. In addition, the staging of the Period Rooms by directors added a narrative layer to the interpretation of the costumes. Not only did they re-capture the design philosophies of the original costume designers, but they also offered their own commentaries from a contemporary perspective. Spanning across two hundred years, from as early as 1805 and as current as 2022, the exhibition extended a cordial invitation to the visitors to glance at the complicated development of American fashion, narrative, and identity.

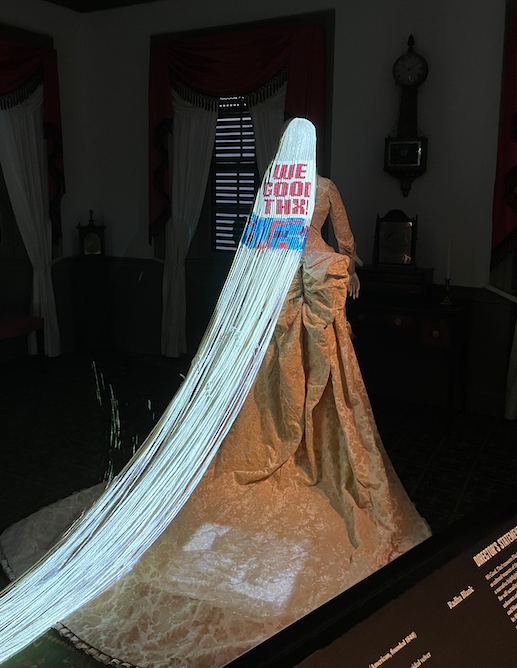

The first major theme we identified for the exhibition was the intersection between black and female empowerment in the fashion scene. In the 1805 Haverhill Room, director Radha Blank staged a wedding dress by the designer Maria Hollander, who founded L.P. Hollander, one of the representative fashion firms in Massachusetts during the 1840s. Maria Hollander herself was a successful business woman and fashion entrepreneur, leveraging her business achievements to further advance women’s rights and abolitionist movements.

The wedding dress showcased Maria Hollander’s fine custom design details and illustrated the high-fashion silhouettes popular among the Bostonian merchant families in the 1800s. Also on display was a pro-abolition quilt she commissioned for an exhibit in New York in 1853. In response, director Radha Blank created her own “quilt” expressing genuine black identity, created as a wig with African American-style braiding and beading that reads “We Good. Thx!” In Blank's scene, she reasserts the autonomy of black craftswomen and adds another layer of contemporary critique to Maria Hollander’s original abolitionist statement.